Drop culture: The wild history & exciting future of product drops

Today, the world’s biggest brands regularly engage in collaborations and product drops. But just a few decades ago, product drops were unknown and unused in retail. Discover how product drops grew from an underground streetwear brand in Tokyo to being embraced by the world’s biggest luxury fashion houses, sneaker brands, and social media companies. Learn the origins of drop culture, and the product drop story of brands from Supreme to GOODENOUGH to Adidas to Louis Vuitton.

This year, Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS dropped a collaborative collection with Austrian crystal company Swarovski. Puma teamed up with ASAP Rocky and Formula 1 on a limited drop. IKEA partnered with Swedish House Mafia to drop audio equipment. Tiffany & Co. x Fendi, The North Face x COMME des GARÇONS, New Balance x Aimé Leon Dore—the list goes on and on.

Product drops and brand collaborations have become an unstoppable retail trend and a marketing force to be reckoned with.

But fashion drops aren't just enabling brands to generate awareness, hype, and loyalty, they’re also perhaps the only sales delivery method that’s produced a subculture.

So, what is drop culture?

Drop culture is the thinking, behavior, and community of customers and brands that embrace product drops. You can see drop culture in action every time a hyped brand releases a limited-edition item. These products are discussed on social media and forums, seen on rappers and influencers, and release to huge fanfare and queues—both on and offline.

Drop culture is closely related to sneaker and streetwear culture. It's spawned its own communities, billion-dollar companies, media outlets and forums, and jargon.

Drop culture gave us the “sneakerhead”, a person obsessed with buying and collecting sneakers; and the “hypebeast”, someone who closely follows trends and acquires hyped products. It’s also produced terms like “don’t sleep” meaning don’t forget a product drop, and “cop” meaning to buy a hyped item.

But it wasn’t always this way. Just a few decades ago, the term “product drop” didn’t even exist. The idea of collaborations between fashion brands—let alone rappers and fast-food and furniture brands—was unthinkable.

In this article, we investigate how the product drop trend became what it is today. You’ll learn about its humble origins in Tokyo, how Supreme rode the product drop wave to a multi-billion-dollar valuation, how sneakerheads and hypebeasts grew out of drop culture, and how brands across industries use drop culture marketing to capture attention, boost their brand, and build communities.

RELATED: Everything You Need to Know About Product Drops: Strategies, Benefits & Examples

While product drops in retail picked up steam in the late 20th century, the basic model behind them goes back a long way.

Product drops take the ticketing model into retail. The nature of ticketing is an event occurs over a limited time span, and the amount of people that can attend—seats available in the theater, stadium, etc.—is also limited.

Similarly, product drops typically only occur once, and involve the sale of products where supply is limited.

Like ticketing, hype drops create scarcity, competition, and urgency for buyers. If you aren’t there when the ticket or product releases, if you aren’t willing to queue and work for it, you probably won’t be able to buy it.

Because of the mismatch between supply and demand, ticketing has always inspired hype and large queues. It’s the first industry that saw scalping and reselling on a wide scale.

Today, the product drop model creates these same effects for retailers. And as these retailers increasingly shift to ecommerce, they’re seeing the contemporary versions of these—social media hype, virtual queues, and bots and resellers.

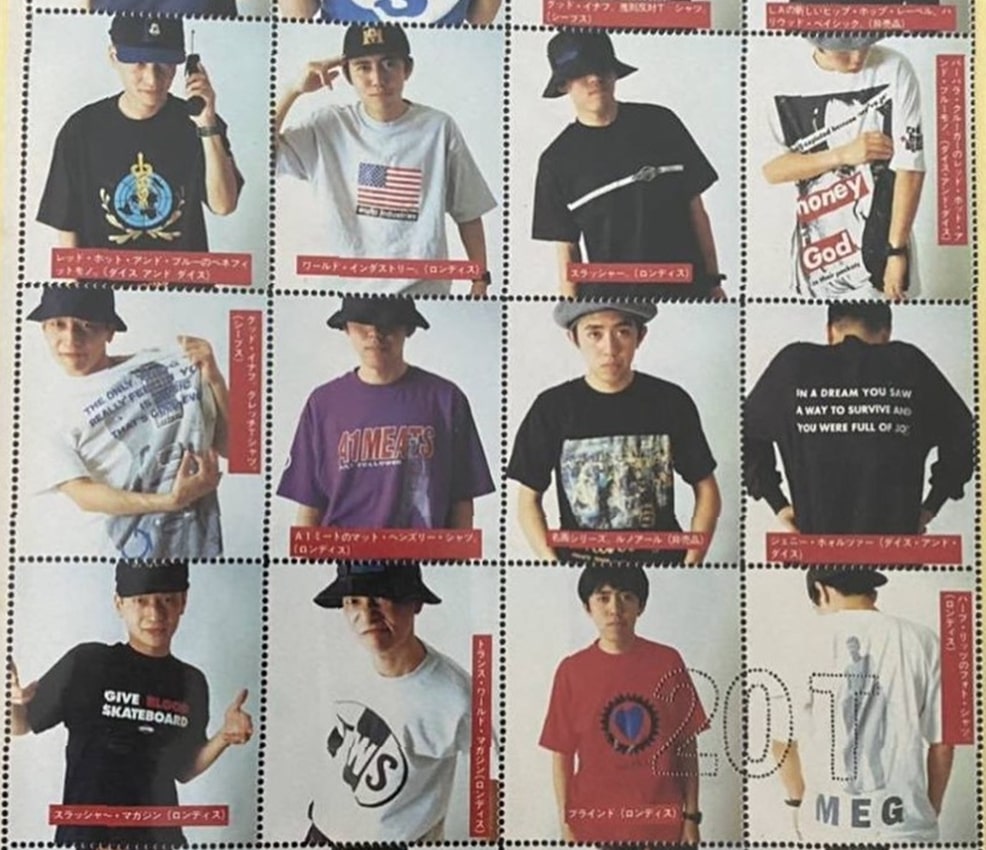

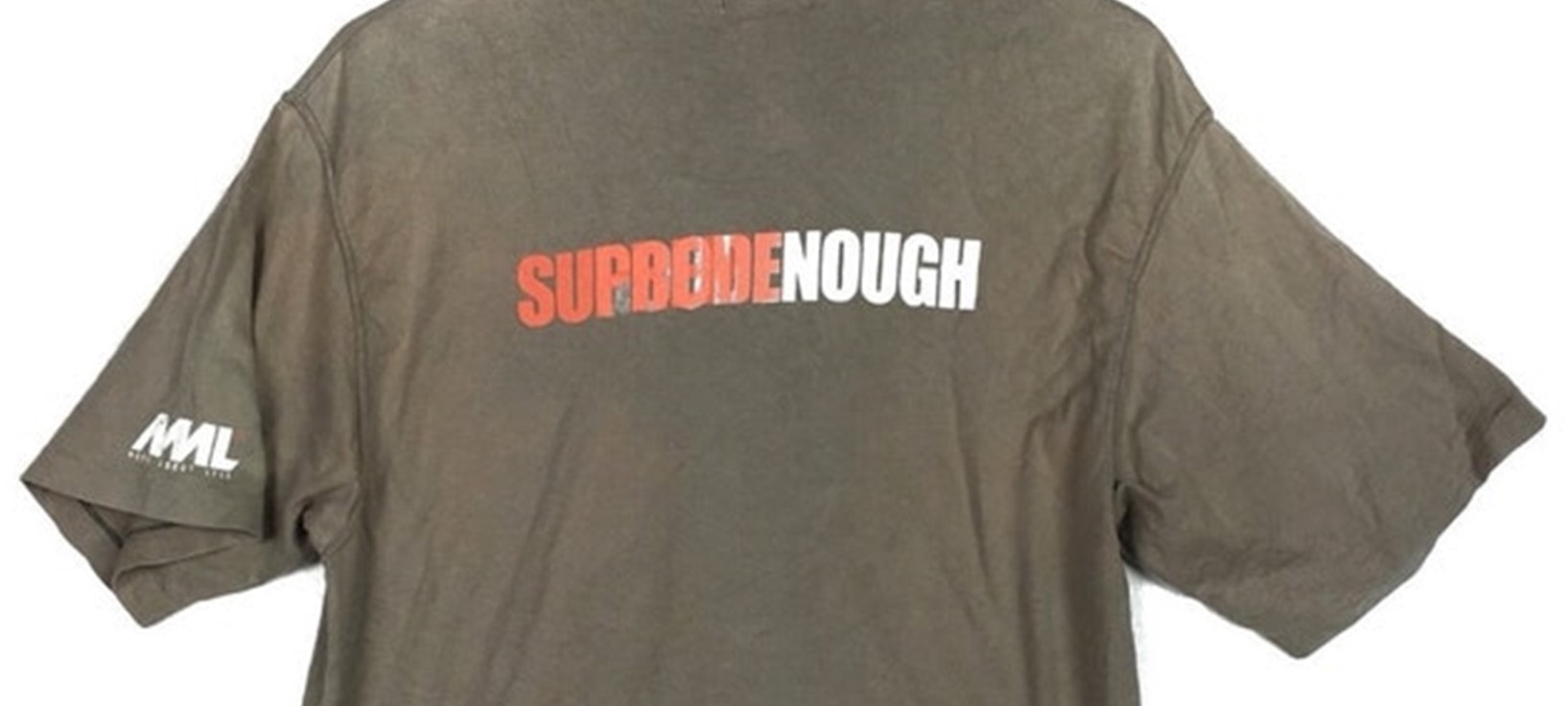

Japanese streetwear brand GOODENOUGH (abbreviated as GDEH) is the first retailer to put a drop strategy at the core of their business model. Hiroshi Fujiwara, who founded the brand, is recognized by many as the godfather of streetwear, and has since collaborated with Louis Vuitton, Nike, Rolex, Levi’s, even Starbucks and Eric Clapton.

Founded in 1990, GDEH took influences from hip-hop, skater, and pop culture across the globe. The brand produced casual garments like graphic t-shirts, sweatshirts, and jackets, but imbued them with exclusivity and luxury with high price tags and regular releases of one-off limited-supply apparel.

It wasn’t fast fashion or high fashion; GDEH was something new. The brand grew a cult following in Japan, with releases consistently selling out and the clothes acting as a status symbol for trendy “in-the-know” youth of Tokyo.

Around the same time, on the opposite side of the world, a similarly trendy underground skate shop called Supreme opened its doors in New York. Like GDEH, Supreme fast became part of the New York skater subculture.

Supreme dropped one-off, limited-supply apparel and skateboards and grew a base of loyal customers for whom the brand represented a counterculture community. Donning Supreme clothing served as a silent “if you know you know” nod to other skaters.

The two brands attributed with starting the product drop phenomenon teamed up for a limited-edition graphic tee in 1999. This set the tone for the collaborative drops that would launch Supreme into the mainstream. It started the hyped limited-edition brand collaboration trend that would take over retail.

RELATED: 27 Successful Product Drop & Brand Collaboration Examples for Inspiration

While GDEH and Supreme were quietly clothing cool subcultures, sneaker madness was growing among hip-hop and basketball fans.

Many cite Nike’s Air Jordan 1 as the first hyped sneaker drop. Released in 1985, the shoe achieved cult status after the NBA told Michael Jordan it didn’t meet regulations and he couldn’t wear it. Nike saw a marketing opportunity and offered to pay the $5,000 per week fine. Jordan wore the shoes game after game, and the rest is history.

While Nike wasn’t limiting supply of Jordan sneakers—as they do today—the shoes grew in infamy nonetheless. The higher price tag of Jordans and their association with the greatest basketballer of all time made them into a status symbol and hot-ticket item.

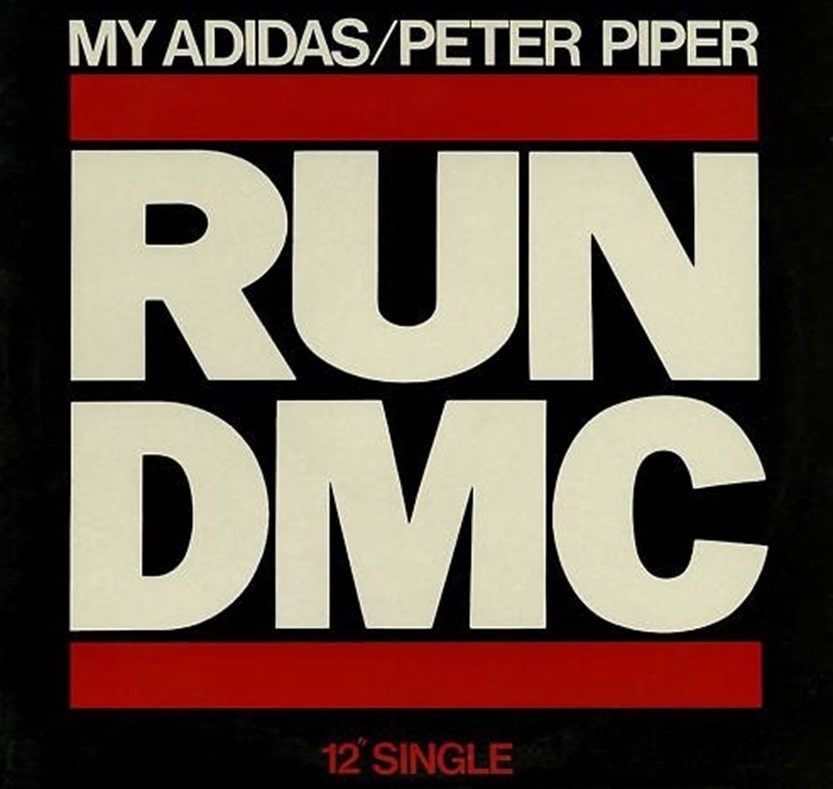

While Jordans were the in-demand shoe for basketball fans, Adidas Superstars exploded in popularity among rap fans after Run-DMC’s hit song My Adidas.

In a now-famous story, Run-DMC invited an Adidas executive to their concert at Madison Square Garden in 1986. The group asked the crowd to hold up their Adidas clothes and shoes as they performed My Adidas. The executive was blown away, and Run-DMC secured a $1 million deal shortly after.

While today brands from Sony to McDonald’s to Dior to Apple collaborate with rappers, the Run-DMC Adidas endorsement deal was the first major partnership between a sneaker brand and a rap group.

After selling half a million pairs of Superstars the year of the endorsement deal, Adidas expanded the partnership further with a Run-DMC line of the shoe and a sponsored tour.

By the early 2000s, several Nike and Adidas sneaker silhouettes reached cult status, and the brands began looking for ways to make these old silhouettes fresh again.

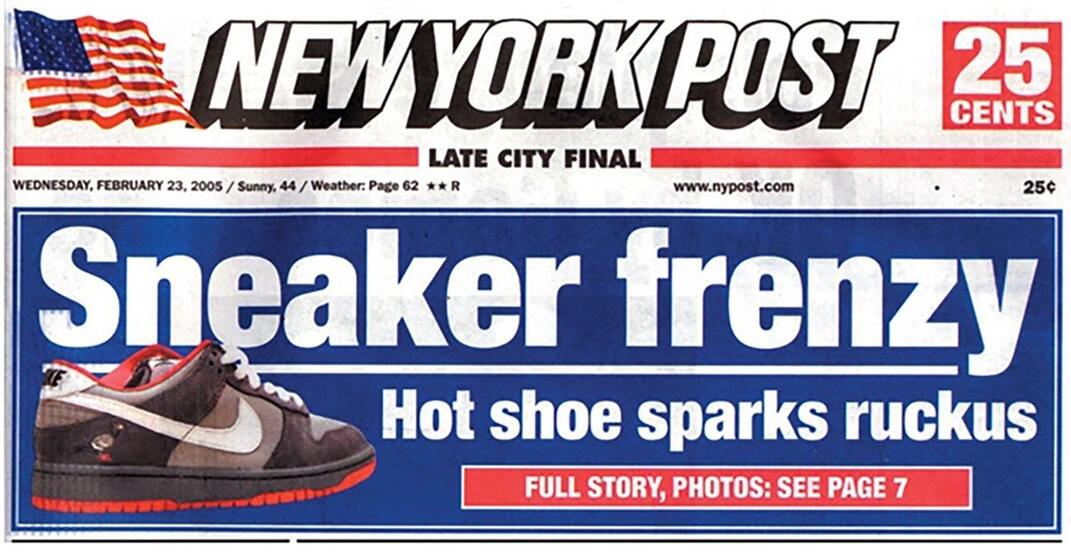

Hoping to corner the growing skater market, Nike rebranded their Dunk Basketball sneaker into the Nike Dunk SB (skateboard). But the skater market was dominated by brands like DC, Vans, and Globe, and sales of Nike SB were poor.

To gain credibility in the eyes of the skater community, Nike pulled the Nike SB line from major stores, and instead decided to stock them exclusively at specialty skate stores. They realized recognition from these stores would transfer to recognition from the skater community.

In 2002, the steetwear drop trend met with the rising hype around sneakers when Nike and launched their first collaboration with Supreme.

This was a Nike sneaker release, but in true Supreme fashion, only 1,250 sneakers were made. They were released—fittingly, considering the origins of drop culture—exclusively in New York and Tokyo.

Rumors of the sneaker’s release spread through word of mouth alone and Supreme couldn’t keep the shoes on their shelves.

It was a win-win. Supreme was co-signed by one of the world’s biggest brands, and Nike was co-signed by one of the world’s coolest brands.

Those 2002 sneakers are now worth over $10,000. And Nike and Supreme collaborations continue to this day.

Hyped collaborative drops became a regular occurrence in the 2000s for streetwear and sneaker brands alike. Drop culture as we know it today emerged. For sneakers and streetwear alike, people traveled long distances to stores, queued overnight, and sometimes even started riots.

RELATED: The Power of Anticipation Psychology & How To Use it for Ecommerce Marketing

Throughout the 2000s, Supreme set the standard both for product drop collaborations and for limited-edition drops going beyond just streetwear.

Their releases proved the true power of hype and scarcity by generating demand over any limited quantity product they put their logo on. Supreme famously sold branded crowbars, bricks, metro tickets, and toothpaste.

This Supreme brick is going for over $300 on resale marketplaces today.

Supreme set another fashion drop standard by announcing an entire collection, then releasing select items from the collection once a week, every Thursday. With this, Supreme’s hype cycle was drawn out over longer periods. Customers who missed out once felt they still had a chance and would return the next week.

RELATED: The 5 Powerful Brand Benefits of Product Drop Marketing

Byron Hawes, author of the book Drop, tells of the sense of community, loyalty, and brand engagement these streetwear drops inspired during this period:

"We would go up to Palace, or wherever Supreme would drop, and kids would literally be there all night. It’s like a new Star Wars movie or something,” Hawes says. "There’s an aspect in it that I found really interesting, in that there’s a sort of sense of community or camaraderie. It’s the same people every single time. Every single person knows every other person. There’s also an aspect where it functions almost like a music festival and maybe like a fashion show, the way high-fashion people do things during fashion week. You can see where street culture doesn’t typically have that kind of thing, but these kids will pay for rarest, rarest clothes."

Oops, you dropped something. Here you go: it’s your free interactive product drop checklist

By the 2010s, most sneaker brands were dropping limited-edition models, and many streetwear began emulating Supreme’s exclusive drop model.

With the widespread adoption of social media and the internet, local communities grew into global communities and niche trends and subcultures spread worldwide.

A lot happened for product drops in the 2010s:

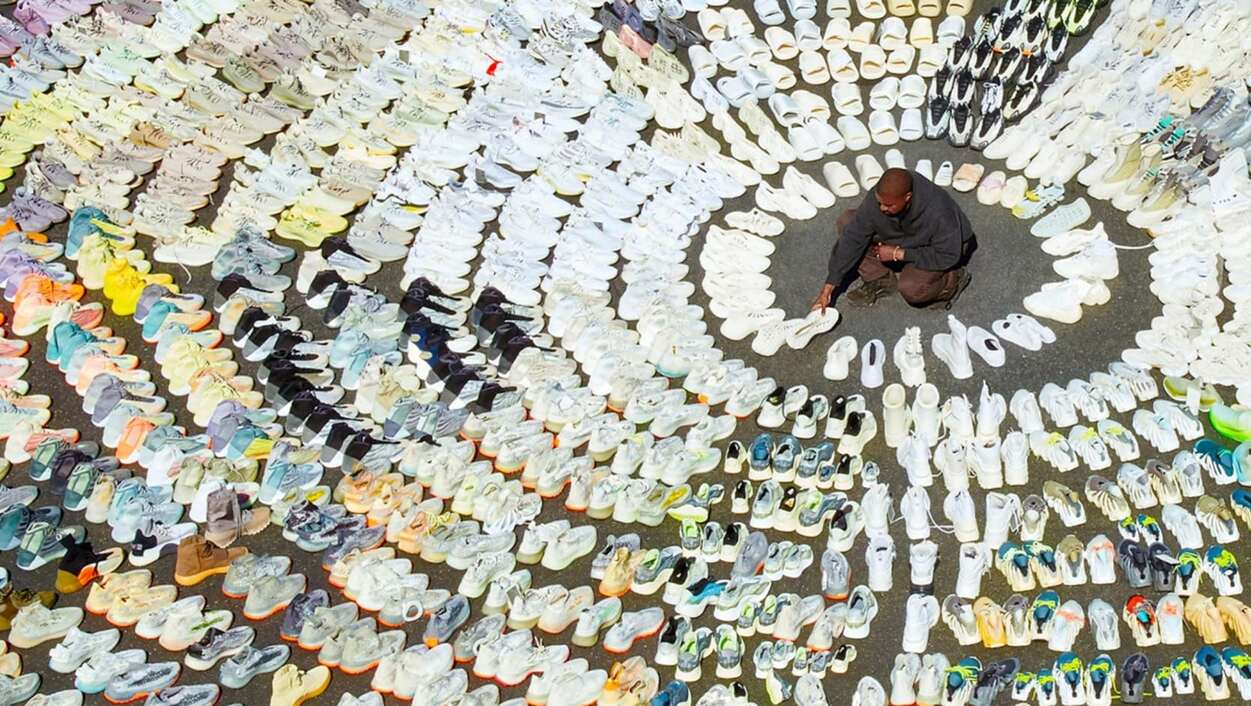

- Kanye West partnered with Adidas on the hugely successful Yeezy brand.

- Nike and Adidas launched apps specifically for sneaker drops.

- IKEA dropped a collection with streetwear icon Virgil Abloh.

- Outlets focused on streetwear and youth culture like Complex and Hypebeast shot to mainstream success.

- Secondary marketplaces like Grailed and StockX launched to cater to the resale market for hyped items.

Kanye West with his Adidas x Yeezy sneakers

RELATED: 7 Simple Scarcity Marketing Strategies to Supercharge Ecommerce

But in terms of bringing product drops to the wider retail space, the 2010s were Supreme’s decade.

Successful partnerships with FILA, The North Face, Comme des Garçons, Champion, and Levi’s, along with an ever-growing customer base and an international reach, proved Supreme’s streetwear drop model worked.

The true landmark moment for product drops and streetwear came in 2017 with the collaboration between Supreme and Louis Vuitton.

Louis Vuitton is the luxury brand. And it went from hitting Supreme with a cease and desist for using their logo in 2000 to launching an official collaboration with the skate brand less than two decades later.

The collaboration was a massive success. So much of a success, in fact, it almost never happened.

Fans camped out for days before the exclusive drop and police in LA and NYC had to shut down the events. Louis Vuitton reportedly canceled the release, then they thought better of it, and set a new date. As you might expect, the high fashion drop sold out almost instantly.

This collaboration marked Supreme’s entry into another realm of fashion and relevance. The once underground skate brand was bought shortly after for over $2 billion.

But the collaboration also reinvigorated the Louis Vuitton brand. For young streetwear fans and tastemakers, it marked the separation of Louis Vuitton from the heritage brand with the logo strewn across rich people’s handbags. It made Louis Vuitton cool again.

Louis Vuitton was clearly pleased with this. They continued to chase that relevance and hype among streetwear culture by hiring architect, designer, and long-time creative director for Kanye West (another product drop pioneer), Virgil Abloh as their artistic director of menswear less than a year after the collaboration.

In an almost exact description of what the Louis Vuitton Supreme collaboration drop achieved, Louis Vuitton’s chief executive, Michael Burke said of the hire: “Virgil is incredibly good at creating bridges between the classic and the zeitgeist of the moment.”

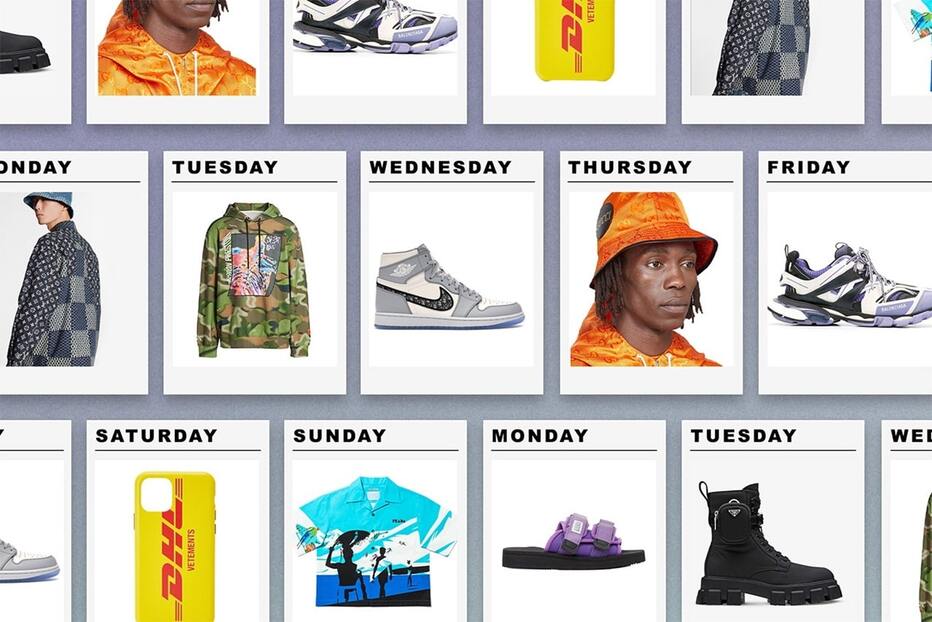

After the Louis Vuitton and Supreme collaboration, brands everywhere begun limited-edition collaborations.

New Balance adopted a product drop collaboration strategy that saw them produce the hottest sneakers of 2022. McDonald’s dropped a collaborative meal with Travis Scott that led to ingredients shortages. Kim Kardashian launched the SKIMS brand entirely through a product drop model.

Product drops went from an underground subculture in Tokyo to being embraced by the world’s largest fashion houses and sneaker brands. Today, the drop trend is a mainstay of major fashion brands, but has also made it's way into other industries. And the product drop model is at the heart of many new brands.

Source: Hypebeast

We established the prominence of drop culture marketing in the 2020s at the outset of this article. It's not only taken over the fashion industry, but is also spreading into the food industry, furniture, software, gaming, and much more.

Exclusive drops bring scarcity and urgency to an ecommerce world where consumers can shop whenever and wherever they want. They enable brands to generate hype, nurture loyalty, and keep customers wanting more.

But as product drops cater to an increasingly international audience and more and more brands choose to run drops online, new versions of the issues faced in the early 2000s—riots, massive queues, scalpers—have emerged.

Instead of being shut down by police due to riots, fights, and noise complaints, online product drops are being ruined by levels of traffic sites can’t handle. The sometimes hundreds of thousands of customers that try to access hyped product drops crash major sites from Nike to Gucci to Walmart.

Instead of dedicated scalpers camping out all night to purchase products to for resale, sophisticated developers use shopping bots to snatch up inventory. The new versions of security guards during product drops are bot mitigation and prevention solutions.

And instead of the long queues outside stores, brands are increasingly turning to virtual waiting rooms (digital queues), to build hype and ensure fairness. Virtual waiting rooms work not only to prevent website crashes by controlling the flow of online traffic, they also filter bots and bad actors, allowing retailers to deliver a fair and reliable product drop experience.

(This blog has been updated since it was originally written in 2022).